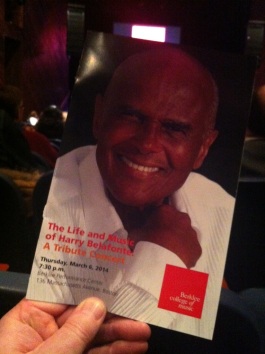

Seeing Belafonte @ Berklee yesterday couldn’t help but make me think back to the time when he came to our NPR studios in 2001 to record a couple of programs around a project that was near and dear to him….but took nearly 4 decades to produce!

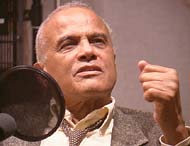

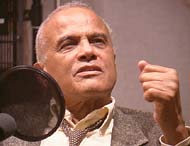

Harry Belafonte at NPR in October 2001 (Photo: David Banks, NPR)

It was called “The Long Road to Freedom,” and aspired to be nothing less than an authoritative anthology of black music in America…from the earliest war crys, work songs and shouts, imported from Africa, to Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man,” and a musical setting of a speech by MLK called “I’ll Never Turn Back No Mo.” Once completed, it contained no fewer than 80 tracks across 5 CDs, as well as a beautifully-produced 140-page hardbound book of photos, essays, and commentary about the black musical experience in America.

It was an amazing, lavishly packaged, and carefully produced set, which Belafonte had undertaken at the height of his popularity in the early 1960’s. Belafonte had the run of RCA’s thoroughly “modern” studio facility, and as a Music Director the legendary (and now shamefully forgotten) arranger and choral director Leonard De Paur, famed at the time for his work with the pioneering De Paur Infantry Chorus, an all-male black chorus that became a top-drawing attraction for Columbia Artists in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

Leonard De Paur, Joe Williams, and Harry Belafonte reviewing a take, C. 1961

And, at the start, Belafonte and De Paur had a budget big enough to bring in some big names to the exercise into chronicling what the singer called “African-matrixed music,” Bessie Jones, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and Joe Williams.

And Belafonte was deeply invested in the project: “We in America know very little about the history of our nation, especially as applied to the black experience,” he said in an interview. “So I always felt that my mission was to use music as a way in which to impart ideas and thoughts that would awaken curiosity.”

But whether is was for reasons of budget, time, or interest, the journey of the Long Road project got a lot longer. The sessions came to a halt around 1971, and the entire project languished in the vaults of RCA – and its ever-evolving corporate ownership – without a single note from any of the sessions making its way to the public. My guess is that at some point, the bean-counters at RCA decided that the ROI would never be realized; the project got put on the shelf, and then institutional amnesia took over.

But, miraculously, three decades later, The Long Road to Freedom materialized in much the form that Belafonte and De Paur imagined it — if not more so. (Ironically, the set was released on Sept. 11, 2001, which may help to explain why it did not get more attention when it was released…). So after a lot of back-and-forth negotiations, one crisp autumn day Harry Belafonte was at NPR, recording a Morning Edition interview with Bob Edwards, cutting tracks for a long documentary special I was producing around the anthology, posing for photos with practically everyone in the building, and sitting down for one of the most extraordinary lunches I’ve ever had in my lifetime.

It actually started the moment we left the building on Massachusetts Ave. for our half-block-walk to the restaurant. Harry Belafonte does not blend in to the crowd; the man oozes charisma. Truck drivers, pedestrians, and even bike messengers all had to say hello to The King of Calypso, which meant that our half-block walk took about 40 minutes. As for the meal itself: the food was profoundly unmemorable, but the the conversation anything but. There is no such thing as “idle chatter” with Harry Belafonte. It wasn’t just the fact that Belafonte has been an eyewitness to history – he had a way of describing his arguments with JFK, or his bailing MLK out of jail, or visits to Africa that were both sharply etched in a journalistic sence, but also deeply philosophical. And he wasn’t content to just tell war stories; like many people of real greatness, he asked as much as he answered. And when Harry Belafonte leans into you and asks you a probing question, you don’t dare give a dishonest response! For all of his struggles for racial equality, you could tell the Belafonte remains a curious and optimistic student of the human condition. Reminds me of how he quoted from Paul Robeson in his acceptance speech at Berklee:

“It’s a wonderful path to be in the arts, because artists are the gatekeepers of truth. Art is the radical voice of civilization.’ From that time until now, I always knew that I would have a life in the arts. My pursuit was to do what Robeson said, take advantage of this gift of art and to develop myself, and to apply it the way other people needed to be inspired.”

Back to the Long Road for a moment: Over time, this collection has become an invaluable resource for schools, critics researchers, documentarians, and, yes, a radio producer or two….though the early-sixties aesthetic of the recordings and arrangements is very much a product of its era. Some of it can sound a little quaint to our ears, but other parts are breathaking, like hearing Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers singing Kneebone Bend, or Belafonte himself doing Boll Weevil You can listen to the interview Harry did with Bob Edwards here.

(Aviso: it’s from 2001, back when NPR was using RealAudio, and it may not play on your fancy smartphone….)

You must be logged in to post a comment.